|

Challenges of renewable power capacity addition is different from that of conventional power. Fast price reductions make past projects look unattractive. Grid integration challenges need to be addressed with special measures. In Andhra Pradesh, accelerated deployment of renewable capacity during 2015-2018, policy changes after massive capacity addition and major policy shifts after government change in 2019 pose a different kind of challenge. This update analyses the impact of these policy flip-flops, based on a study of the renewable energy generation, especially wind and solar, during the period 2014-15 to 2019-20. It concludes that renewable capacity addition planning requires special attention, knee jerk policy shifts are not good for the sector and a stable regulatory regime is essential – not only for renewable, but for the whole electricity sector. |

1. Introduction

Power purchase accounts for 75-80% of the total cost of Distribution Companies (DISCOMs) in Andhra Pradesh (AP), and is the toughest challenge in sector planning and operation. Long term contracts with costly thermal power plants pose one kind of challenge. Accelerated deployment of renewable power poses another kind, the subject of this update. Renewable power related challenge is due to the fast changes in technology and tariff, as well as the complexities in integrating it with the grid. Multiple changes in policies and priorities, either based on hindsight or due to change of government, can make the situation worse. Flip-flops on renewable energy generation policies have resulted in many complex challenges in AP. This update analyses the impact of these policy flip-flops, based on a study of the renewable energy generation, especially wind and solar, during the period 2014-15 (FY15) to 2019-20 (FY20).

2. Brief overview of renewable energy in AP

This section gives a brief overview of Renewable Energy (RE) in AP, covering the key data trends from FY15 to FY20 and major policy changes, especially after the government change in Jun 2019.

2.1 Data trends

Around 9,000-10,000 MW of solar and wind capacity was proposed to be added by FY20 as per the AP Power For All agreement, solar policy and wind policy prepared in 2014-15. At that time, solar and wind capacity was only around 700 MW. The policies included many incentives, concessions and must-run status for solar and wind projects. As per an order of the Government of AP (GoAP) in Nov 2015, Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was to be formed with Suzlon and Axis energy to set up wind, wind-solar hybrid projects (adding to 4000 MW) and wind turbine manufacturing facilities in AP.3 Solar projects were to be based on competitive bidding.

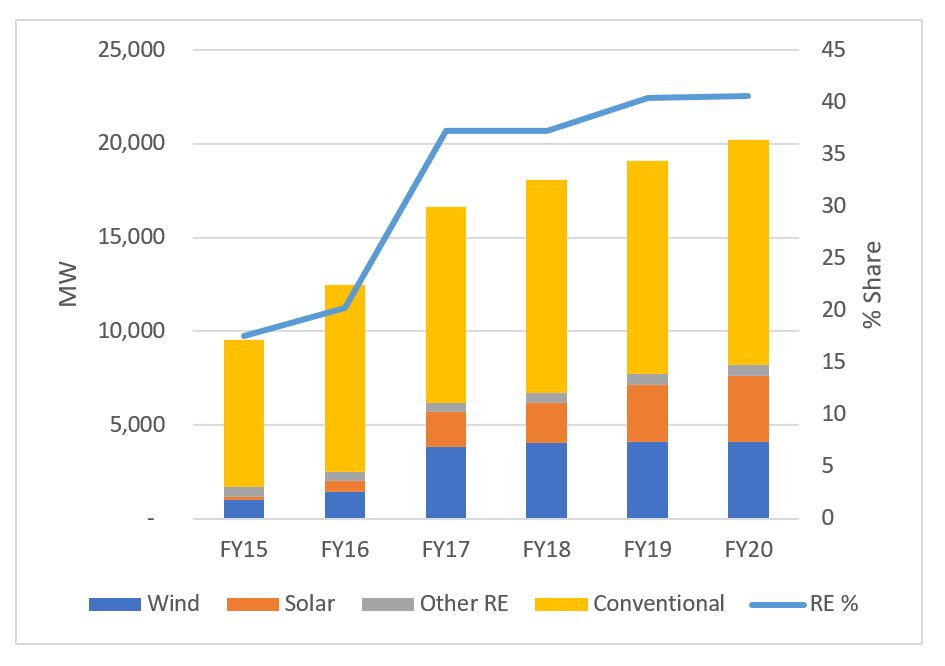

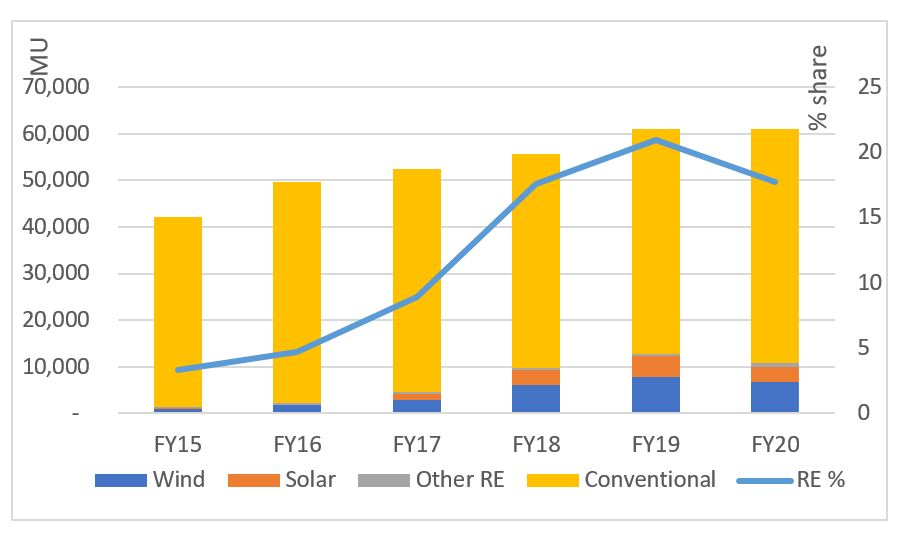

Figure 1 shows the trend of installed generation capacity from FY15 to FY20. It can be seen that the share of renewable energy sources (wind, solar and other RE) in the total capacity has been steadily increasing, from 18% in FY15 to 40% in FY20, with the biggest increase between FY16 and FY17. The trend of energy purchase, as shown in Figure 2, is also similar. The share of energy purchase from renewable sources steadily increased from 3% (FY15) to 18% (FY20), with the biggest increase between FY16 and FY18. The share of RE generation was higher than the Renewable Energy Power Purchase Obligation (RPPO) targets for all the years – for example, the target set in the 2017 RPPO regulations of AP Electricity Regulatory Commission (APERC) for total RE was 13% for FY20, and the actual generation was 18%. Same was the case for solar (target 5%, actual 5.3%) and non-solar RE (target 8%, actual 11.2%). Capacity and generation of other RE sources (small hydro, bio-mass, bagasse and waste to energy) increased only marginally during the same period, FY15-FY20.

Figure 1: Trend of installed capacity

Source: Compiled by Prayas (Energy Group) from APTRANSCO Annual power sector development report 2017-18, Power sector monthly fact sheet for March 2020 and March 2021

From Figure 1 and 2, it can also be noted that wind capacity addition during FY16-17 contributed to the rise in renewable energy share significantly, and that solar capacity addition has been gradual over the period.

Figure 2: Trend of energy purchase

Source: Compiled by Prayas (Energy Group) from DISCOM tariff submissions (for FY15, FY16, and FY20 – submissions made two years ahead) and True-up order for FY17,FY18 and FY19

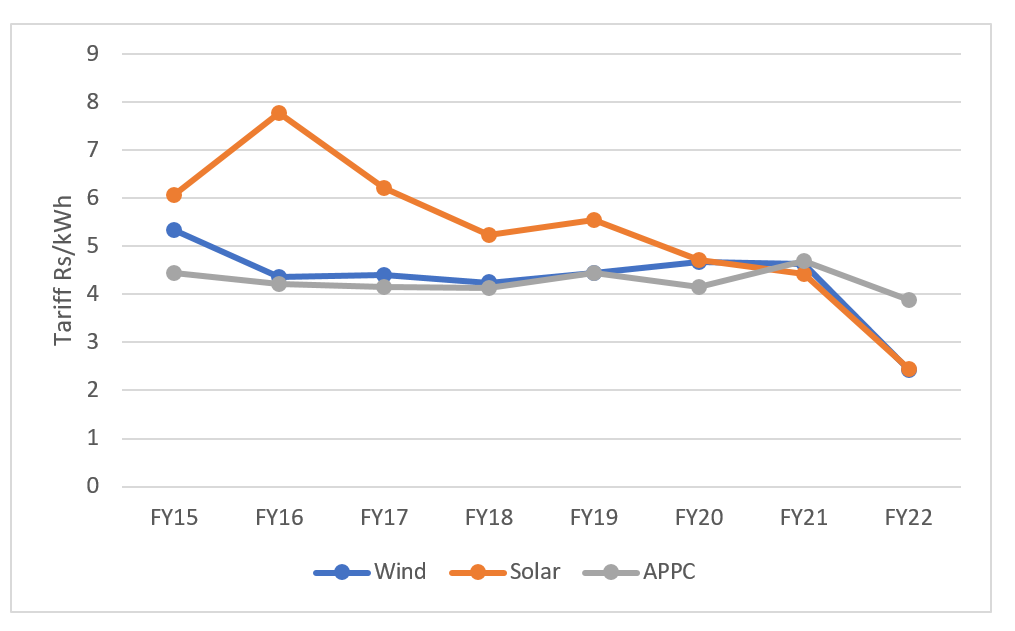

Tariff of renewable sources has been high in AP. Figure 3 shows the trend of actual average power purchase cost (tariff) from wind and solar sources from FY15-FY20 as well as the APERC approved tariff for FY21 and FY22.4 It can be seen that these tariffs have been consistently higher than the average power purchase cost, except in FY21 and FY22.5 High capacity addition before the tariff reduced, not adopting competitive bidding for wind projects, issues with bidding of solar projects and relatively small capacity of solar and wind projects could have led to high tariff.6

2.2 Policy trends

There was high level of enthusiasm to add renewable capacity from FY15 till FY18 – wind through feed-in tariff and solar through bidding. Since RE had must run status, the tariff orders had approved full dispatch schedule. The deviation of actual annual dispatch from this schedule was quite low at 1 to 5% in the years FY16-FY19, whereas it started increasing from FY20 (33%).

Figure 3: Trend of average tariff

Source: Compiled by Prayas (Energy Group) from DISCOM tariff submissions (actuals data for FY15, FY16, and FY20 taken from submissions made two years ahead, True-up order for FY17,FY18 and FY19 and approved tariff from tariff orders for FY21 and FY22

AP was the first state in India to notify solar and wind forecasting, scheduling and deviation settlement mechanism regulations, as early as in Aug 2017, implement it and start preparations for a separate renewable energy management centre in the state load dispatch centre. But the issues of quick RE (mostly wind) capacity addition in a short period of around 18 months with high tariff, leading to RE generation share higher than RPPO targets and higher power purchase costs, were raised in many public hearings. It is also to be noted that the wind manufacturing facilities, as envisaged in the wind policy (2015) and Memorandum of Understanding with wind developers, were not set up.

There were some signs of change in approach from 2017, and the Distribution Companies (DISCOMs) filed a petition with APERC in March 2017, requesting to curtail the multi-year feed-in-tariff regulation for wind. As per the 2015 regulations, feed-in tariff for wind was to be annually determined by APERC for the period FY15-FY19. In its order issued in July 2018, APERC agreed to curtail the regulation control period from five to two years. Since the central government had released the wind competitive bidding guidelines, APERC also said that after April 2017, DISCOMs have the option of purchasing wind power through competitive bidding as per the 2017 guidelines (prepared by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) Government of India (GoI), or through feed-in-tariff, guided by the 2017 regulations of Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC). There was no wind capacity addition after this. GoI had issued tariff policy in 2016, which suggested competitive bidding for solar and wind. This was followed by the tariff based competitive bidding guidelines for solar and wind in 2017. Solar projects had adopted competitive bidding from 2011 through the National Solar Mission, and the wind projects also adopted it from 2017. Solar tariff in the country had dropped to Rs. 2.97/kWh in Feb 2017 and wind tariff dropped to Rs. 2.65/kWh in Oct 2017.7

Based on the objections during tariff public hearings, in February 2019, APERC wrote a letter to Government of AP (GoAP), requesting it to obtain legal opinion of the Advocate General of AP on the possibility of reviewing the Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and reducing the duration from 25 years to 5 years.8

State elections were held in April 2019, in which the ruling TDP party lost and a new government led by YSRCP party took office in June 2019. There were many major changes in RE related policies and plans after this event, as summarised in Table 1.

The twists and turns in RE generation in AP after 2019 are clear from the table, which captures some major developments related to RE generation as well as some new initiatives. RE curtailments, payment delays, move to review of RE PPAs and amending policies have led to many court and regulatory cases, which have not concluded as of August 2021. The final order from the AP High Court is awaited, there are ongoing cases in Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (ATE) and APERC.9 There are many complaints about non-transparent curtailment of RE projects. ATE order on solar curtailment in Tamil Nadu, issued in August 2021 had raised this issue and has issued clear directions (to all DISCOMs, SERCs and Load Dispatch Centres) on conditions for curtailments and compensation for undue curtailment.

A relatively smaller issue is about the two changes in the allocation of RE capacity to DISCOMs. The 2014 AP reorganisation Act had allocated RE generation to DISCOMs as per geographical location, which was reasonable considering the low RE capacity. But as the RE capacity increased, mostly in one of the DISCOMs (AP Southern Power DISCOM – APSPDCL), in 2017, the GoAP allocated RE capacity in the state to both DISCOMs in the power sharing ratio used for sharing thermal generation. This was justified on the basis of balancing power purchase cost and renewable power purchase obligations. Surprisingly, in October 2019, the GoAP reversed this order with retrospective effect, without citing any reasons.10

The RE developers complain about opaque curtailment and payment dues, while the utilities have been raising issues like costly RE power, grid integration challenges due to high RE capacity and inaccurate generation forecasting by RE projects. These issues are being debated in court and regulatory cases. But the current government has taken up plans to quickly add more renewable capacity through initiatives like AP Green Energy Corporation (10 GWp solar)11 and RE export policy (2020, planning 120 GW capacity) covering wind, solar, wind-solar hybrid projects) and pumped storage hydro projects.12

Table 1: Key developments in AP RE after Apr 2019

| Date | Event |

| Apr-Jun 19 | State elections in Apr-19, New government assumes office in Jun-19 |

| Jul-19 | Government of AP (GoAP) sets up Ministerial Committee to review high priced solar and wind PPAs and bring down the prices through negotiation |

| Jun-Jul 19 | Letters to GoAP from Government of India suggesting not to review PPAs |

| Jul-19 | Solar and Wind developers file Writ petition in AP High Court against PPA review |

| Aug-19 | Curtailment and payment dues to RE projects start increasing |

| Sep-19 | AP High Court (APHC) common order by single judge, setting aside the move to review PPAs, fixing interim tariff, asking APERC to decide the final tariff |

| Nov-19 | GoAP amends solar and wind policies - removes many concessions. There was no clarity on effective date, and this was clarified in Mar 2021, as Nov 2019 |

| Dec -19 to Mar-20 | In tariff petitions for FY21 filed in Dec-19, DISCOMs request additional subsidy if RE is to be dispatched. Tariff order for FY21 dated Feb-20 does not accept DISCOM suggestion, but the DISCOMs submit review petition with APERC |

| Jun-20 | GoAP sets up AP Green Energy Corporation (APGECL) to install 10 GWp solar capcity for agriculture supply |

| Jul-20 | RE Export policy to expand RE capacity to 120 GW for export |

| Nov-20 | DISCOMs submit tariff petitions for FY22, including RE |

| Mar-21 | APERC issues tariff order for FY22, including RE, but at interim tariff as per High Court order |

| Apr-21 | APERC sets up three-member expert committee on RE curtailment |

| Aug-21 | Chief Justice bench of APHC starts hearing appeals on curtailment, payment dues, and single bench order asking APERC to set tariff |

Source: Compiled by Prayas (Energy Group) from GoAP orders, APERC tariff orders and AP High Court case status information

3. Lessons

There are three major lessons from this saga of flip-flops in RE in AP state – the need for special attention to RE power purchase planning, the dangers of sudden policy changes and the crucial need for a stable regulatory regime – not only for RE, but for the entire state electricity sector.

3.1 Special attention to RE power purchase planning

RE power is different in many ways from conventional thermal power, the traditional main-stay of AP generation. Transmission planning and maintenance is as important as in the case of conventional power. The modularity and fast technological advances in RE imply that competitive bidding based gradual capacity addition is to the advantage of the consumer. There is also a case to promote distributed RE, since it has some advantages over centralised RE. Measures to meet the grid integration challenges have to be planned along with RE generation and associated transmission. This includes specific measures in storage, forecasting, load management and grid management. Unfortunately, AP did not give this kind of special attention to RE capacity addition. It must also be noted that there are similar issues related costly thermal capacity addition and backing them down, but that is not the focus of this update.

During the period FY15-FY19, RE capacity addition was driven by the PFA agreement, solar policy and wind policy. These were not prepared after any transparent public processes. At a time when RE prices were rapidly dropping and competitive bidding was being introduced, there was no justification to opt for rapid RE capacity addition, especially through MoU route for wind. AP lost out on the benefits of tariff reduction and technology improvements due to this.13 There were issues in transmission planning and maintenance, as evidenced by the wind curtailment enforced due to issues with the transformers and transmission system around Uravakonda substation.14

The complexity of grid integration was high, since Forecasting & Scheduling regulations and arrangements for grid balancing (like State electricity grid code, storage facilities, flexibility in thermal dispatch, dispatch modelling) were either absent or not stabilised. These issues were raised in public hearings, but mid-course corrective actions were not initiated, until too late. Even then, what was done by utilities was requesting for government subsidy for RE or large-scale curtailment of RE. Such measures only compound the planning shortcomings, rather than overcoming them.

A robust process for long-term power purchase planning and short-term operationalisation is essential. The load forecasting and resource planning exercise was delayed and first order was issued by APERC in 2019 for 2020-24, by which time, most of the capacity addition had already taken place. Since many major changes took place after 2019, there is an urgent need for a mid-term review of this plan.15 Power purchase cells in DISCOMs and AP Power Purchase Coordination Committee (APPCC) have to be strengthened and made professional with more staff and modelling tools.16

3.2 Dangers of sudden policy changes

Major policy and priority shifts, either in hindsight or after government change do not make the state RE friendly.

Even if one considers that 25-year contracts with costly RE was a mistake, the solution is not to dishonour the conditions (like must run or timely payments) or attempt to review the contract terms. Such measures would discourage future investment as developers and investors perceive increased risks. If sanctity of contracts is not maintained, it sets a precedence for not honouring contract terms, some of which may be in consumer interest. As renegotiation takes time, along with the uncertain outcome through litigation, there will be interest cost burden which consumers have to bear.

Feed-in tariff through MoU route for large capacity wind was not a good idea, but removing the RE concessions through policy amendments only compounded the problem.17 After finding many issues with existing RE, planning for massive solar capacity addition for agriculture supply or export, without a transparent planning exercise, amounts to the repetition of similar mistakes. Going by the history, one cannot rule out demands for review of these initiatives after a few years.18

3.3 Need for a stable regulatory regime

The final and perhaps the most important lesson is about how the RE sector and the electricity sector should be treated over long periods of time and when the political regime changes. The APERC and AP State Load Dispatch Centre (APSLDC) have crucial roles in this.

During the years FY15-FY19, APERC played limited role in RE capacity addition. It went by the PFA agreement or DISCOM proposals to approve the wind PPAs and adopt the solar tariff. When APERC made an observation in a solar contract order that PPA conditions could be reviewed, an ATE order overruled it.19 APERC did bring out a regulation on RE forecasting and scheduling, which was implemented reasonably well till FY19. There is a need to strengthen the implementation of this regulation and bring out an updated State Electricity Grid Code.

There were complaints of RE curtailments implemented for commercial reasons, whereas the grid code permits it only for grid security. SLDC started reporting curtailment data on its website from August 2019 (after a directive from the High Court in Aug 2019), but the details are limited.20 So much so that the ATE order of 12/8/21 asked SLDC to submit curtailment details to POSOCO, who are to verify if it was really due to grid security issues. This is not a good indication of the credibility and autonomy of SLDC, and it is high time that it is separated from the state transmission company, as envisaged in the Electricity Act 2003.

The new government which took office in 2019, accused the previous government of mismanagement and corruption on many infrastructure projects – building the new capital, irrigation schemes and power sector. Electricity sector is a key infrastructure sector, with key links to economic and social development. It has long lead times, with projects taking years to be planned and completed, and impacts to be felt over decades. It is reasonable to expect that changes in political perception can lead to changes in macro policy, over a period of time. It is also reasonable to investigate cases of corruption. But abrupt reversal of policies, attempts to revise contracts, curtailment and payment delays without due consideration to the implications of such actions, does not augur well for the sector.

To conclude, special attention to RE planning and ensuring a stable policy and governance environment are essential for RE sector to develop in AP. This must be evident to consumers and citizens. But unfortunately, the RE sector is in the midst of numerous regulatory and court disputes. It is best if the existing issues are sorted out by the state power sector actors, rather than by courts or central government institutions. We hope that the government, utilities and the developers realise this even at this late stage. It is high time that they took a comprehensive long-term view of the sector and worked together to share the cost of previous actions, repair the broken bridges and plan a healthy future. APERC can play a significant role in adjudicating on this thorny issue, while SLDC ensures secure grid operation with transparency.

Endnotes

1. Author thanks BN Prabhakar and D Ramanaiah Setty (both from SWAPNAM - NGO), colleagues Ashwin Gambhir and Ann Josey for valuable comments on the drafts and Sharmila Ghodke for data support. Author is responsible for this final version.

2. This article is part of an ongoing series called Power Perspectives, which provides brief commentaries and analysis of important developments in the Indian power sector, in various states and at the national level. Comments and suggestions on the series are welcome, and can be addressed to

3. GO MS 15 dated 27/11/15 (Energy, infrastructure and investment department), available at GoAP GO site.

4. These are average power purchase cost numbers. For wind, the generic tariff determined by APERC was Rs.4.83/kWh (FY16) and Rs.4.84/kWh (FY17)

5. FY21 and FY21 data are APERC approved numbers, not actuals. Also, in FY22, APERC decided to approve the lower RE interim tariff (Rs. 2.43/kWh for wind and 2.44/kWh for solar) as per the September 2019 order of the AP High Court.

6. As per the website of New and Renewable Energy Development Agency of AP (NREDCAP), as of March 2021, total wind capacity was 4084 MW from 194 projects and total solar capacity was 4018 MW from 158 projects.

7. Source: Prayas RE portal costs and prices. Solar was the MP 700 MW bid and wind was the SECI 1000 MW bid.

8. Reason cited was that during the public hearings for FY20 tariff order, stake holders had raised the issue of reduction of tariff for wind and solar projects elsewhere in the country.

9. AP High Court order of 24/9/19 by single judge on Writ Petitions 9844 and others (2019) and case status of the ongoing Writ Appeals 190 and others (2020) with the Chief Justice division bench can be accessed at the AP HC case status website. ATE cases include wind power curtailment, on which orders have been issued in 11/9/20 and 12/8/21, and ATE order dated 27/2/20 directing APERC not to review competitively bid solar PPAs. APERC had set up an expert committee to study RE curtailment through its order on 16/4/21, but the final report is not yet public.

10. GO RT 118 dated 21/7/17 allotted RE capacity in power purchase share and RT 116 dated 1/10/19 allotted as per geographical location. Orders of Energy and Infrastructure department available at GoP GO issue website.

11. AP GO MS 18 of the Energy and Infrastructure department dated 15/6/20 (available at AP GO issue portal) has the details of AP Green Energy Corporation, a subsidiary of AP Generation Company, which would facilitate setting up 10 GWp solar plants to supply power to all agriculture pumpsets in AP.

12. Proposed wind and pumped storage projects are available at the website of NREDCAP, which indicates 17.8 GW wind and 6.3 GW pumped hydro. On 17/8/21, Economic Times quoted the AP Energy secretary that 33.24 GW of pumped storage projects are planned.

13. From the Wind tab in Prayas RE portal: Wind tariff discovered immediately after adoption of competitive bidding for wind Rs. 3.5/kWh (Feb 2017, SECI 1000 MW), went as low as 2.43-2.45 in 2018 (GUVNL, SECI) and is now around Rs. 3.

14. RE curtailment is a long story in itself. The issue of wind curtailment from 2017, due to issues of the transformers at 400 kV substation at Uravakonda (a town in Anantapur district) and nearby transmission lines, crucial for evacuation of half the wind capacity in AP, is documented in APERC site visit report of 2019, ATE 2020 order upholding 70% curtailment order of APERC and ATE 2021 order directing for transparency and analysis of curtailment by the national load dispatcher POSOCO.

15. For more details, refer the Load forecast and resource plan order of APERC and Andhra Pradesh Overview in Prayas Power Perspective portal.

16. APPCC was till recently headed by the Chairperson of the transmission company with representations from DISCOMs, but by order MS 5 dated 30/7/21, GoAP has made the energy secretary the chairman of APPCC with others as members. Such direct concentration of power purchase with the government is not a healthy move.

17. In Nov 2019, government removed many RE concessions (like waiver of wheeling charges, banking facility) given in the 2018 RE policies, but it was not clear when this would be effective (GO MS 15, dated 18/11/19). It was in Mar 2021, that government clarified that this amendment is applicable for projects commissioned after Nov 2019 (GO 1, dated 1/3/21). GOs available at GoAP GO issue website.

18. In Dec 2020, bidding for 6,400 MW solar capacity for AP Green Energy Corporation was done. Five developers were selected, with two of them having 80% of the capacity. Tariff was in the range of Rs.2.48 to 2.58/kWh, when the SECI/GUVNL bids around the same time were around Rs.2/kWh, though it is not totally appropriate to compare.

19. This ATE order dated 27/2/2020 was on appeal by solar developers arguing against the Oct 2019 APERC order, which suggested reviewing PPAs in a competitively bid project.

20. APSLDC website gives brief details of written curtailment instructions to wind and solar. The time block, MW backed down and brief reason (in few words – like high frequency) are given. A cursory analysis of this indicates that wind curtailment is around 20-100 MW and solar around 100-400 MW.