|

Appointing mediators between a regulator and a private party for PPA approval can set bad precedence not just for institutional validity but for public interest as well |

One of the key quasi-judicial functions of Electricity Regulatory Commissions (ERCs) is to adjudicate on disputes. Orders issued through such processes can be taken up before the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity (APTEL) for review and appeals. The APTEL was established under the Electricity Act 2003, with the specific mandate of constituting a dedicated forum with sector expertise to critically review decisions of ERCs. This is an important measure to hold ERCs accountable for their functioning.

Thus, when an appeal is made by an aggrieved party against an ERC’s order, by virtue of its role, the APTEL is expected to either provide a verdict on the matter, or send it back to the ERC for reconsideration, given new insights that it unearths. From thereon, it is expected that the case can be closed through an expedited process. This is, perhaps, what was anticipated when an order by UPERC was challenged by some solar project promoters.

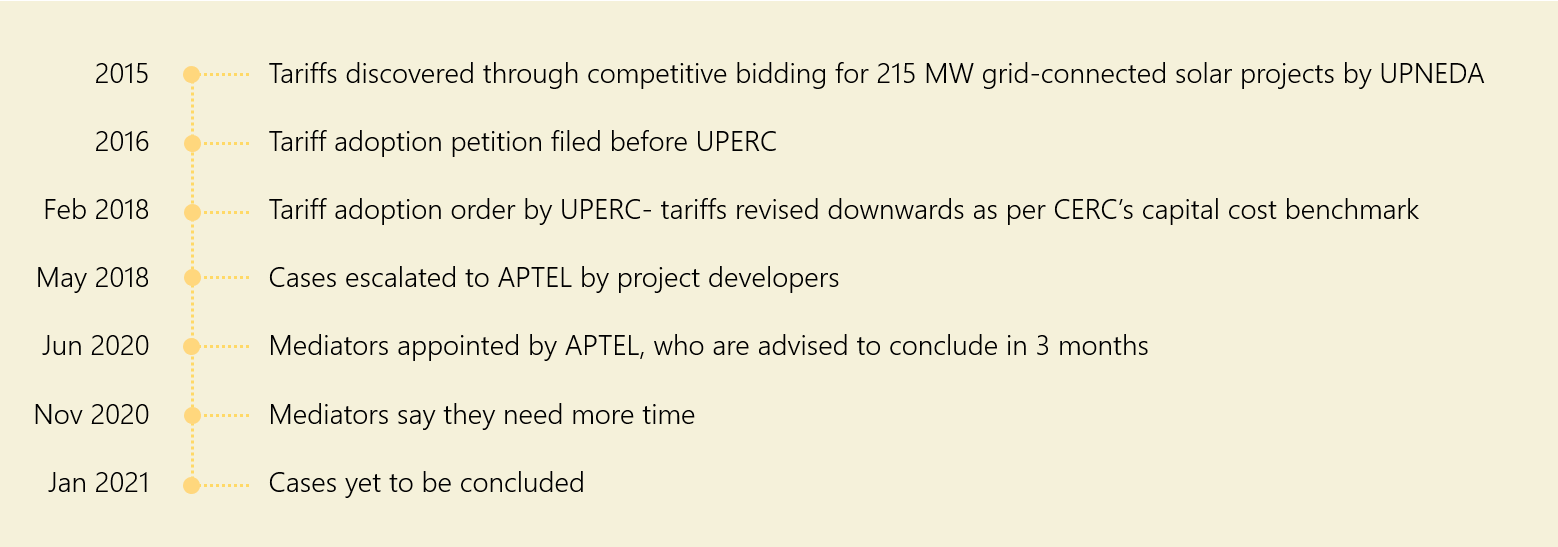

The Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation Ltd. and Uttar Pradesh New and Renewable Energy Development Agency had filed for tariff adoption before the UPERC in 2016 for setting up grid connected solar power plants of 215 MW capacity, soon after competitive bidding was held in 2015. Six of the project promoters approached the APTEL in 2018 when UPERC, while approving the tariff adoption order, revised their tariffs downwards to “reflect the market rates”. Timeline of the cases has been captured in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Timeline of events for dispute resolution of solar Power Purchase Agreements in Uttar Pradesh

Source: Compiled by Prayas (Energy Group) from several regulatory orders

In June 2020, the APTEL opined that cases such as these would be resolved better if “parties could thrash out their differences sitting across the table over a dialogue”. The APTEL had further observed that since litigation can often drag on for years, it would be “practical” to hire mediators since there were “elements of settlement” in these cases. It is possible for a higher appellate authority to direct parties to go through mediation processes. What is strange is when this higher authority directs another quasi-judicial institution to resolve a case through closed-door mediation.

The implication of such a decision is twofold. First, it establishes a basis for decision-making on an issue of public interest through closed-door mediation. The case at hand concerns tariff determination for power purchase–– a cost that is ultimately passed on by the utility to consumers through their power bills. Hence, given that impacts of decisions on power purchase agreements are borne by the end consumer, such cases warrant decision making through public processes. In fact, such a view was upheld by the Supreme Court of India, while hearing a case related to the commercial operation date of the thermal power plant at Sasan.

Second, it undermines the authority and legitimacy of an institution, such as an ERC. Directing the institution itself to sit through a mediation process across the table, with an aggrieved party, does not quite hold the same importance as asking the said institution to review the case in its own courtroom. Further, given that the APTEL was instituted with the very purpose of sector-specific swift decision-making, it is not clear why mediation between a regulator and an appellant would resolve the cases sooner, as was reasoned by the APTEL in its orders.

The question remains if appointing mediators was effective in expediting the process. The cases were filed before the APTEL in 2018. After delays due to reasons such as vacancy in the tribunal, they were actively taken up in 2020, when the tribunal appointed two mediators for these cases. Former judicial and technical members of the APTEL were appointed as mediators, the parties were asked to compensate them, and the cases were to be resolved within three months. Seven months have passed since then, and going by the APTEL’s daily orders, it seems likely that it might take at least a few more months to close these cases.

The cases brought before the UPERC are complex, as most power purchase related disputes are. It involves passing judgement on whether prices discovered through competitively bid processes can indeed be revised by ERCs, to reflect current market rates, during tariff adoption processes, years after such bidding is conducted. The complexity involves ascertaining how much capital has truly been locked-in–– the status of land acquisition, solar module procurement, or setting up of transmission evacuation networks, among others. The APTEL was constituted to throw light on such complexity, hence it sets good institutional precedence if the APTEL gives reasoned orders on such issues, rather than appointing mediators to do the same.

Given its role as a custodian of public interest, and a critical expert reviewer of ERCs’ decisions, the APTEL is expected to reduce ambiguity and provide sectoral direction with its verdicts, which should be based on sound legal principles. Hence, when these complex cases concerning generation projects are brought before the tribunal, giving clear directions, legal analysis and detailed accounts of the APTEL’s reasoning is essential. Such actions would not only aid the swift resolution of these cases, but also create a legacy for similar cases in the future. Directing another quasi-judicial body to enter into mediation doesn’t bode well for sectoral governance.